INTERVIEW

Jason Holley x Matt Cottam

Collaboration across creative fields as a vehicle for knowledge sharing

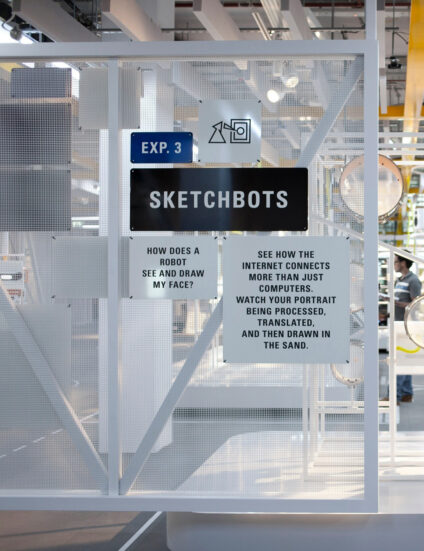

Working alongside Tellart to bridge digital and physical experiments for Google

"We know that the best projects come from close collaboration and that for this project to succeed it had to be collaborative."—Jason Holley

"After two decades of working on these kinds of projects, I’m still not always clear on what makes them work, but it’s definitely something about the people involved – it’s all about the human relationships and how ready people are to set ego aside." — Matt Cottam

"We were very lucky with this project – I remember sitting in the cafeteria at Google one day thinking how exciting it was that we didn’t know where we were going but that everyone was on board for the journey." — Matt Cottam