OPINION

Designed to Last

Lisl du Toit and Elif Duztepe from the Universal team consider how we create lasting spaces that can be sustainable in all senses of the word

Designed to Last

Are radical methods the only path forward for architects and designers in implementing meaningful change when it comes to sustainability and the places and spaces we inhabit? Should we stop putting new things into the world and instead look at how we can adapt and reuse what we already have? And can creatives even enact lasting change without the support of governments and big business? As a design studio that is shaping the way people live, work and play, Universal Design Studio’s Lisl du Toit and Elif Duztepe reflect on what, how, and why we build in the final instalment of our first e-paper series.

If we are trying to create a more sustainable world, reframing our built environments and challenging deep-rooted preconceptions about how architecture operates should become standard. Across the field, we have a responsibility to create lasting spaces that can be sustainable in all senses of the word: environmentally, economically and socially. Tax laws incentivise new builds at the expense of more ecologically sound retrofits; building certification schemes can be onerous to apply across projects of varied scope; and consumer culture valorises the new, promoting the rapid demolition or refurbishment of spaces, all while prioritising futuristic aesthetics whose material choices are rarely grounded in consideration of their environmental impact. With this in mind, we need to rethink our application and programming of spaces, ensuring that we give buildings and spaces the fullest lifecycle they can provide - moving beyond siloed servicing and offering multi-faceted uses for multi-faceted needs. We need spaces that work for the environment and people alike.

If architects and designers are to play their part in meaningful collective action we have to realise that we are not powerless to effect change. There are rigorous steps that can be taken to design buildings and spaces that are not only better for the environment, but better for both our clients and the people who use them. We have the ability to propose designs that can actually meet the high standards we ought to set ourselves, and we have the opportunity to help influence people’s aesthetic tastes, material understanding and behaviours through our work.

We need to be ambitious and demand more of ourselves: sustainability should have a positive impact across society, not just limit the negative impacts of the climate crisis.

Adaptive Architecture

The seismic changes of the past two years have demonstrated that socio-economic changes in our towns and cities are calling for a more open and adaptive approach to architecture. With the decline of the high street, a slow in UK-based manufacturing and the rise, and rise, of the digital economy, we must consider the design of single-functionality spaces as redundant. Revitalising buildings of the past, to meet the needs of our present and address our ever-changing futures can be the most sustainable way of creating new spaces. This approach can also be applied to new buildings, considering any new structure as a place to accommodate multiple functions and programmes - an envelope for activity and not a stage for any one use.

Removing a singular function will allow tenants to thrive on the adjacencies of different uses with diverse possibilities. Can we imagine bringing manufacturing back into the city, and mix it with amenities such as a health service? Can we pursue urban farming and hospitality, producing where we consume? Can a building become a hub for a specialist endeavour, attracting many different tenants from different businesses under one overarching theme?

Looking at existing building stock, the ubiquitous warehouse building is perhaps one of the best examples of adaptive architecture. A familiar architectural relic of the nineteenth century, warehouses graced towns and cities across England and formed the basis of an energetic industrial revolution and a commercial boom. One such example is Manchester, in the north of England, synonymous for its warehouses and associated canals and railway viaducts, all of which were created in the Victorian and Edwardian eras and today represent a new vision for a thriving modern metropolis. Designed as cast-iron and later steel structures with large open floor plans for manufacturing and storage, the buildings lend themselves to increased flexibility. The warehouse has since proven to be a dynamic host for alternative functions, from residential apartments to artists’ studios and rave venues. Relaxed planning restrictions have also helped to completely repurpose these spaces, with carved up live-work units within larger warehouses. When it comes to creating new buildings, perhaps our cities require new versions of these large ‘containers’ to play host to our evolving needs and desires.

Universal Design Studio’s own portfolio has always been rooted in reuse and retrofit where possible, having explored this approach through three hotel projects, all of which developed existing buildings: Ace Hotel in London (pictured below), At Six in Stockholm, and Villa Copenhagen. In all of these cases, revitalising existing spaces has brought sustainability benefits – a lot of carbon has already been used within their construction, and so it represents sound ecological thinking to reuse them – but this is only part of the story. They all also represent opportunities to bring new value to the communities surrounding them.

At Villa Copenhagen, we designed the material strategy to support local Danish industry by working with suppliers and manufacturers close to the city, such that the space becomes enmeshed with – and a showcase for – Copenhagen’s artisans and producers. The spaces also used natural materials such as linen, oak, walnut and European marble, that will age robustly, become more beautiful with time, and can be easily repaired when required. At Six, a hotel project in Stockholm, provided an opportunity to restore a 1970s brutalist structure in Stockholm’s Brunkeborgstorg Square. The space’s scale and fundamental architecture were spectacular, but the building had become derelict and lost its social value. Its restoration and careful updating, complete with bespoke commissions from local makers and Scandinavian designers, reaffirms that there is beauty, social worth, and functionality to be found throughout cities the world over: it simply needs to be uncovered.

Transformation through Design

In 1972, the great 20th-century designer Charles Eames was interviewed by the curator Madame L’Amic for his film Design Q & A. “Design depends largely on constraints,” Eames told his interlocutor. “What constraints?” she replied. “The sum of all constraints,” Eames answered. “Constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time, and so forth. Each problem has its own peculiar list.”

Eames’s answer was grounded in the design discourse of the time, but even today it carries an important lesson. All architecture and design is guided by constraints. Today, we are fortunate to have a deeper, more holistic understanding of quite how extensive those constraints actually are. Our actions have a serious, lasting impact on the environment, and this needs to be factored into all design decisions. We have become aware of more constraints than ever before, and projects need to meet the demands of clients, users and the environment alike. But this is what design is good at. To work seriously as an architect is to engage with the world as it is and to seek to improve it in some form. We cannot simply push forward projects that we may like artistically or theoretically, but which are divorced from reality on the ground. Genuine engagement is vital.

Revitalisation need not be a passive act of restoration. It is also an opportunity to disrupt convention by reconfiguring architectural functions and providing new resources to users. With the Ace Hotel in London’s Shoreditch, our aim was to create a space that served guests as well as the local community. Collaborating with neighbourhood vendors, consultants and manufacturers, a series of restaurants, bars, retail points and co-working spaces were created for the ground floor, resulting in a space that felt reflective of the surrounding area’s culture of art, design, tech and culinary innovation. By offering an open space that was attractive to the local community and actually used by the neighbourhood, Ace Hotel developed an energy that was in turn attractive to those wishing to stay in the hotel. In this sense, a social offering needn’t be something that stands in addition to a space’s business: it can be woven in and actively enhance it. Something that makes sense for a community likely makes business sense too.

As much as possible, any act of creative transformation should future proof a space and ensure that it will remain valid and valuable for as long as possible. We know that our current culture of development hungers for the new: to resist this, we need to create buildings and spaces that give clients as little reason as possible to seek to redevelop them in the future. A major aspect of this work is ensuring that spaces eschew temporary trends and fads, but it is also about designing buildings that are adaptable and flexible enough to change over time, and grow along with the companies and communities who inhabit them. In Tintagel House, The Office Group’s flagship co-working space on London’s Albert Embankment, our design was built around adaptable floor plans which could easily expand or contract based upon occupancy level, ensuring that the space can shift between more open forms of work, or be partitioned into discrete offices. Equally, the public-facing ground floor is designed with moveable partitions and curtains to demarcate space, such that it can easily flex to accommodate working during the day, before opening up to host events or parties in the evening.

Approaching design with this focus on positively transforming existing spaces, and ensuring the long term usefulness of our designs, is not only good in terms of sustainability: it is good design full stop, offering the best possible response to the multiple constraints that forge a project. Throughout architectural history, there is a long list of figures who have offered inspiring, alternative futures, such as Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes and Archigram’s Fun Palace. Speculative design like this is essential and vital, but the radicalness of their presentation should not distract from the practicability of many of their core ideas. Better futures are attainable and we have the ability to bring them into real practice. As designers, we need to rethink how our cities work, how buildings function, and what we can do to change the social structure of the city to encourage more sustainable ways of being. By its nature, architecture transforms spaces: we have the power and responsibility to make sure that the changes we propose are positive ones.

Materials Matter

We can now design and build using a wealth of materials, from hemp and corn husks to recycled plastics and waste from food production. Designers and design-minded brands are leading the way in showcasing how best some of these materials can be used in real-world practice. Alongside this however, is a need to educate clients and consumers alike on where some of these ‘green’ materials have pitfalls. It is important to understand the entire lifecycle of a material; how it is made and then treated to be used in our spaces, as well as the realities of its end of life.

Many of Universal’s working processes centre around materiality and hands-on making, having been founded by British designers Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby, our studio and working culture is organised around our workshop and materials library. This space offers a central repository of samples from a vast range of materials, embodying the team's combined knowledge and expertise, and providing a jumping off point from which we begin all projects. Today, it also represents our best tool in designing conscientiously and responsibly.

Currently, the majority of our environmental impacts are contained in our material choices – if we can improve material literacy, and develop our knowledge of the ecological implications of different materials, we can foster a positive change from the very first stages of projects. Education is the best way to enable this. As part of our studio-wide learning and development programme our Sustainability Working Group meets with project teams early in their design process for this very reason, talking through potential strategies which includes material choices when projects reach this stage.

Collaboration sits at the heart of our practice and our understanding of materials and advancements is bolstered by external consultation with experts such as the Materials Council, independent material consultants to the creative industries. Most recently, our team has been working with the Materials Council on material typology guidance. Honing in on specific categories such as metals and timbers, the Materials Council is guiding us on how best to specify sustainably within these categories. By selecting material typologies that our team uses most frequently, our ambition is to have a real impact relatively quickly in our projects.

Although design teams can opt for the most sustainable choices, value engineering phases of projects can see some of these adapted or designed-out for profitability. Equally, retrofits often face unforeseen costs, for example a building that may need additional structural support will put strain on the budget elsewhere and this usually means it is difficult to maintain the integrity of the original design. Value engineering can however be tackled by instead cutting out some original material choices altogether, rather than opting to go for lower cost alternatives that are unsustainable. In these instances, designers and architects need to be robust in their bottom line of what we are willing to sacrifice for aesthetics versus sustainability.

The furniture industry is also making bigger steps in the constant annual cycle of new products it presents to the world. Milan Design Week has historically seen hundreds of brands presenting what is likely to be thousands of new pieces for ‘seasonal’ launches. Faced with increasing backlash, brands are now at the forefront of ensuring some of their best-selling products have circularity in mind. Renowned Swiss brand Vitra has been producing timeless designs since the 1950s. One of its more popular new designs is the Tip Ton chair by Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby, originally created in 2011 and manufactured by Vitra. Drawing on established links between movement and learning, but having itself no moving parts, the design uses a slightly angled tilt at the front of its skid base to support two distinct sitting positions. Nearly a decade later and with its design unchanged, the Tip Ton RE was unveiled as Vitra’s first chair to be made from local recycled material, using plastic sourced from the ‘Yellow Bag’ reusable waste programme in Germany.

Designers too are no longer relying on collaborating with brands to instil environmentally sound material principles or manufacturing processes. Fernando Laposse is one such example, an artist who specialises in utilising natural materials to create design pieces, from sisal and loofah furniture to decorative veneers made from corn husks. Beyond highlighting natural material sources with a low environmental impact, Fernando’s work also draws on regenerating traditional agricultural practices in Mexico and by extension micro-economies, regeneration of land and preservation of biodiversity for future food security. The materials we build with are deeply entangled in economic, social and environmental systems, and as demonstrated by Laposse, this can be exploited for the better.

Our studio has recently been part of the team creating the exhibition design for Our Time on Earth (a 2022 exhibition at London’s Barbican that explores the climate emergency), focussing on researching natural materials such as cork, hemp, cellulose and tree bark. These materials bring multiple advantages to spaces, not least the fact that their production can affect both social and environmental change through small-scale regenerative farming methods: processes that carry benefits for biodiversity, soil health and the communities who farm them alike. None of the materials used within Our Time on Earth are revolutionary and most have been present within the design and architecture material palette for a long time: we simply need to remind ourselves that materials like these have valid architectural applications and can bring real value to a space.

Reimagining the role of the Designer

We are mostly engaged once a brief is in place and location has been selected. What would the possibilities be if architects and designers were involved at an earlier stage? We could help to shape what type of location is required, could the client repurpose something existing or would a new build be the best fit? Equally design-led research and strategy develop needs-based responses in a more holistic way. Sustainability is often a ‘tick box’ area of the brief rather than something that is woven throughout the process. If the brief shaping phase involved a diverse set of disciplines it would certainly have a noticeable impact, with the ability to set clear benchmarks for environmental success. Items such as quantifying and measuring embodied carbon and material labelling could become the norm.

Another avenue for longer-term change comes via long term clients. Ongoing client relationships with multiple projects allow us to shift the dial incrementally each time we collaborate, looking at past projects and critique areas for development with the same brand. These bigger briefs help to impart change in the longer term, but there is a level of rigidity in that everything is tied to cost and value. Installations and smaller experimental projects often provide the best ground to test new ideas quickly. As creatives, we can be more agile in our responses and methods as there is less at stake from a cost standpoint.

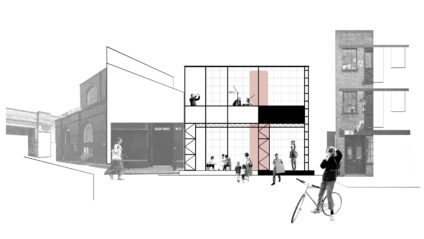

‘Framework for Exchange’ was our pavilion for the 2018 edition of the London Design Festival, created in collaboration with The Office Group (TOG), its aim was to encourage creativity, community and collaboration through the different forms of exchange that shared work spaces organically promote. The temporary, two-storey pavilion was constructed from scaffolding and occupied the courtyard at the entrance to TOG’s building in the heart of Shoreditch. Quick to construct— which is vital for festivals such as this when time is in limited supply—scaffolding is relatively cheap and in ready supply. It also gave us a literal framework to store, hang, support and display artworks. By using scaffolding, the pavilion could be assembled, disassembled, recycled and reused over and over. This honesty and singularity to the construction appealed to us as well as the notion that the soul of the pavilion could live on after the festival, existing in other places and spaces throughout the city. The theme of active collaboration and the exchange of knowledge, skills, time and goods was explored through the pavilion’s architectural language and in the pavilion’s events programming.

The role of the designer need not result in tangible outputs. During last year’s London Festival of Architecture, our studio teamed up with OPO to create ‘Still in the City’, an augmented digital experience that blended soundscapes and eyes-open meditation with the built environment. Titled ‘Still in the City’, OPO and Universal sought to reinvigorate the relationship people had with London, following a series of lockdown periods in the fight against Covid-19. The ambition was to provide a renewed appreciation of what the built environment can do for people, highlighting how we can drop into peak moments of wellness in daily urban life.

Harnessing the diversity of London’s architectural landscape, Universal curated 12 locations, each of which celebrate the variety of architectural history in the city and where we can appreciate the beauty of the built environment. OPO in turn curated 9 site-specific meditation soundscapes which the public could download to listen to and experience. Once at a location, a session unlocked in the OPO app.

The meditation was an eyes-open session which encouraged the public to rest their attention on certain architectural and natural points in their view. Mapping these points together created the perception of a ‘room’ in our mind that supported us to drop deeper into a place of presence and contemplation, ideal for meditation. The project highlighted how we can leverage technology to fulfil some of our ‘spatial’ needs, in this instance helping to create a ‘meditation room’ of sorts using existing structures.

The Design Process

Centring sustainability in the full design process is pivotal if architects are to fold environmental practices into our everyday work, rather than keeping them as a siloed off corner of design or a tacked-on, box-ticking exercise. To achieve this, we need to grapple with its complexity. There is no one-size-fits all solution. Every project requires a nuanced approach and rigorous decision-making when it comes to choosing how and where to deploy materials and forms. Different projects lend themselves to different strategies and even a useful metric such as embodied carbon only tells a partial story. A material that has a low embodied carbon, but which cannot be recycled or reused, makes little sense if used in a temporary project or an area of architecture that typically sees a high turnover of spaces, such as retail. Likewise, materials with a higher embodied carbon may sometimes be justified, particularly in spaces that call for durability.

In 2015, Universal created the design for 2°C, an exhibition looking at the communication of climate collapse initiated by the design journal Disegno at London’s Aram Gallery. As the exhibition focussed on the climate crisis, it needed to uphold the values it espoused, and not simply pay lip-service to sustainability. Particularly given the show’s temporary nature, it was critical that 2°C’s design engage deeply with the problems it raised and prioritise materials that could be reused or repurposed in order to avoid wastefulness. As such, rather than simply pick materials that looked or felt “green” to visitors, we launched an extensive material research programme that ultimately settled upon a temporary framework made from plywood sheets. We focussed on standard sized sheets to ensure future reuse and, so as to not punch holes in the wood, created a system of belts and straps to hold the material in place such that they would not be permanently marked. Every design decision in the process was orientated towards making the exhibition architecture dismountable and reusable. Once 2°C had finished its run, the unaltered plywood pieces were disassembled and employed in other projects.

Although plywood’s production undoubtedly carries ecological costs, it brings other advantages. Given plywood’s ubiquity, it was possible to source the sheets from close by to the exhibition, preventing excessive transportation, and by selecting a standard, widely used component we ensured a meaningful afterlife for the material. As designers, we need to consider the whole story: a project often requires a more creative, deeply thought through solution than the one you may instinctively pursue due to training or current industry trends. During the design process, it is key to adopt a perspective that can continually zoom in and out, such that we address both the micro details that make a project work, while still being sure it can perform sustainably at the macro level.

In 2010, Universal created the interior for Mulberry’s New Bond Street store. As part of this space, the team worked with the engineers Max Fordham to create a drystack stone wall that could function as a form of air conditioning: making use of stone’s thermal massing properties, the wall is able to retain heat when required, or else help cool the space. Twelve years on, this stone wall is still in place, and has significantly reduced the operational energy usage of the store during that time. Alongside this, it stands as an embodiment of Mulberry’s brand identity, which is heavily tied to the English landscape, ensuring that it meets the client’s needs and can remain in situ long-term. Because the system was grounded in a clear material rationale, it still feels fresh and contemporary even today.

Embedding this kind of sustainability in the design process demands collaboration, both within the studio and with external stakeholders. Sustainable design requires a community effort, so bringing clients along with us for all these decisions is key. We can create something less wasteful by treading lightly in the case of temporary projects and investing in sturdy yet flexible designs for more long-term spaces. If a client makes this journey through the decision-making process, understanding the value of what they are committing to, they feel invested in making choices that may eschew a flashier design in favour of a more thoughtful, effective one. Building relationships with clients beyond a single project allows for a more holistic way of working; as trust and mutual understanding grow, we can push the parameters of a sustainable design process.

We are currently undertaking a project of this nature with Schoups, a law firm based in Antwerp who are expanding and sought an old building to give new life to. The 1960s eight storey building was formerly used by the Antwerp police and is located on one of the main routes leading into the centre of the city. The building sits between two heritage buildings: the Neo - Romanesque style Heilige Geest Church and the Beaux arts style Mago Academy for music.

Universal’s team worked closely with ONO architects, artist Philip Aguirre y Otegui and landscape architect Ludovic Devriendt on the scheme, in a highly collaborative process that involved everyone in key decisions, regardless of discipline. The project celebrates the aesthetic of the existing concrete structure by exposing it wherever possible and the envelope is updated to be more energy efficient. While the front facade gives back to the city through artwork by Aguirre y Otegui, the rear considers the non-human users of the site, leaving gaps to be inhabited by local bats. In a bold move, the clients approached the adjacent church to demolish a boundary wall and transform what was a parking lot into a shared garden open to the public. Rainwater will be harvested from both buildings to maintain the garden and solar panels have already been installed to provide a shared energy supply.

Stakeholder involvement and understanding is also crucial to avoid undoing sustainable choices implemented earlier in the design process. Building projects are complex and unforeseen expenses inevitably crop up, for example it may be discovered during construction that an existing building needs costly additional structural support. If the client understands the rationale they would be more open to exploring solutions that don't sacrifice sustainability.

Within the studio, we uphold our values of transparency by encouraging open discourse. Learning from each other, and acknowledging that each design project is part of a wider ecosystem. If we are struggling with a design, we talk it through with one another. If something in a project could be improved, or one team has devised a way of working that taps into the circular or sharing economy, it’s important that we share our learnings. Thinking together and collaborating creates richer solutions for the problems we are currently facing.

Rising to the Challenge

Architects alone cannot solve the climate crisis, but through holding ourselves accountable and collaborating with one another and colleagues from across the industry, we have the potential to affect change. We can design spaces that will responsibly serve people now and for decades to come.

One part of this complex puzzle is a focus on the materials we use in our work. Material literacy has always been essential to the discipline, but we now have the opportunity and responsibility to push this further than ever. At Universal, our materials library allows us to demonstrate the qualities of low carbon materials to our clients. We can take meaningful action by championing more sustainable materials and taking the command decision to remove materials from use when their environmental cost is too great in comparison to their performance.

This attention towards materials is the first step in weaving sustainability into our entire design process. By applying sustainability principles rigorously, and in a fashion that pays attention to nuance and the individuality of all projects, we can create work that is ideally suited to its planned lifecycle. Temporary spaces can be taken apart and repurposed, while long term projects make the most of durable and appropriate layouts and materials. Key to this is fostering long-term relationships with clients that are built on trust and confidence: together, we can promote a sustainable decision-making process that forgoes trends in favour of flexible, human-centric design.

By acknowledging the importance of constraints towards design, and seeing their potential to help produce sophisticated, real-world spaces, we can lead on campaigns to prioritise retrofitting and refurbishment projects where possible. As architects, we should enjoy the challenge of breathing fresh life into existing spaces: it can be a challenging approach, but one which represents the future of architecture in many cases. As well as promoting sustainability, this methodology can bring more to cities by carving out spaces that support clients, the environment and communities alike.

Sustainable design is not something that has to be staid, predictable or formulaic. It is an act of creativity that has the potential to shape our futures for the better. Sustainable design is good design. It is design which lasts, which takes into account the needs of future users as well as those in front of us today, and which does not settle for simply trying to maintain the status quo, but which pushes the industry towards making a more lasting positive contribution. Caring for the environment is an act that spans yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Our 'Designed to Last' principles

Design for people not trends

Enduring design won’t come from chasing fleeting trends. Give projects longevity and authenticity by putting people at the heart of the design process.

Work with care and respect

Respect each other, but also the materials that are moulded into spaces. Respect also includes building in plans for ongoing care and maintenance, such that timeless design can last as long as it should.

Be transparent, open, and critical

Share successes – and failures – to promote collective progress. Open discussions in the studio and with external collaborators to allow for the pooling of knowledge that can help avoid unwitting greenwashing.

Think together and be collaborative

We cannot do this alone. The climate crisis is big and complex, and can’t be addressed if everyone works in isolation. Combining different perspectives and alternative angles on problems gives us the best chance of success. Key to this is collaboration – both within the industry and by extending a hand to other disciplines.

Be brave and visionary

Imagining and offering up alternative futures requires creativity. Maintaining current systems and ways of working is not enough, and we need to push the envelope so that our future spaces are programmed responsibly and with sustainability at their core.